RSA with CRT Part 2: Implementing Fast RSA

This post is the second in a two-part series about recently implemented optimizations to speed up performance of our open-source, embedded RSA implementation. Read part one here.This post will cover the actual implementation of RSA CRT key generation and modular exponentiation. Our implementation focuses on correctness, maintainability and performance.

Now that we have a sense of the math behind RSA CRT, we might wonder what a practical implementation looks like. Besides correctness, real RSA implementations need to contend with practical matters like limited compute resources, long-term maintainability, and certifiability under essential cryptographic standards such as FIPS 140-3.

We’ll cover not only the path to implementing CRT modular exponentiation itself, but also the fine technical details of working with limited memory and high register pressure while remaining performant and avoiding timing side-channels.

While performance is essential for any deployed cryptographic implementation, certifiability is also critical, as standards like FIPS can are often important requirements of commercial opportunities. As such, we’ll highlight the technical nuance in how we maintained FIPS-compatibility while performing this significant optimization.

To get a sense of what such a performant, certifiable, and maintainable implementation might look like, let’s analyze our implementation of the CRT optimization for RSA in depth, starting with the changes to key generation.

CRT Key Generation (or, Working with Too Little Memory)

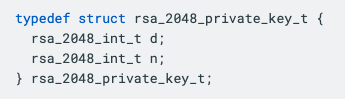

The first step is changing the private key format. In naive RSA implementations, the private keys only need to store the modulus n and the private exponent d, as they just compute ciphertexts/signatures as c = md mod n directly.

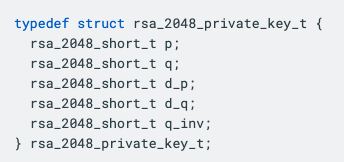

For RSA CRT, we instead work directly with the primes p and q, and need to store the precomputed values dp, dq and qinv. This takes us from a private key format (for RSA-2048) of

to a new CRT format of

Note that we’re now storing five 1024-bit numbers instead of two 2048-bit numbers, so there is an associated 25% size increase to public keys. Since this represents a change in the ABI, as well as an increase in keyblob sizes, it’s essential for changes like this to be made prior to the initial release of a cryptographic library, preventing reverse compatibility breakages that could have severe impacts on users.

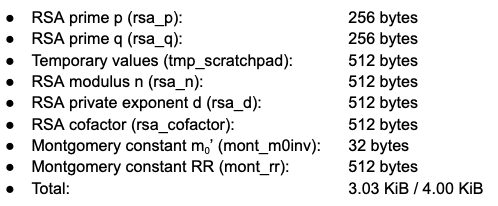

Along with changing the key format, we also need to change the key generation routines to output the values (p, q, d p , d q , q inv ) instead of just (n, d). When writing programs for our asymmetric cryptography accelerator (based on the OpenTitan BigNum implementation), we start by carving up the data memory (“dmem”) into the regions that we’ll be using for storage of different values. Depending on the generation this data memory can be as small as 4 KiB. Previously, the data memory allocation looked like:

(Some parenthetical details: the rsa_cofactor buffer is for inputting a cofactor (either p or q) to reconstruct a RSA keypair; this is handy for importing keys. The mont_m0inv and mont_rr buffers are precomputed constants for Montgomery multiplication, a fast modular multiplication algorithm that helps speed up the generation of primes p and q.)

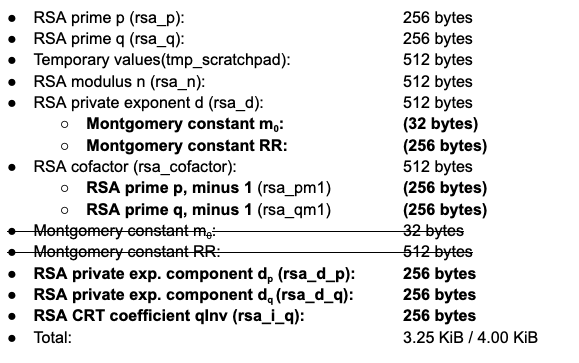

Now that we also need to compute d p , d q and q inv , as well as track other intermediate values, our new dmem memory map looks like (overlapping buffers shown as sub-bullet points)

which just barely keeps the data memory overhead small enough to allow e.g. for the auxiliary buffers that tests use. Note that some buffers are used multiple times; for instance, the Montgomery constant aren’t used after computing p and q, so we can reclaim that space for storing d later in the key generation routine.

The careful eye might catch two lines above that look somewhat silly; why are dedicated buffers rsa_pm1 and rsa_qm1 needed for storing p - 1 and q - 1? The answer is that the least common multiple function overwrites its inputs to reduce dmem overhead. If we just subtracted one from rsa_p and rsa_q in place, as the prior key generation code did, the LCM computation would clobber the primes in each buffer, resulting in garbage values for p and q in the generated private key.

Next, let’s look at the actual changes to the algorithm. The prior key generation approach looked something like

- Generate random primes p and q

- Compute n = p * q

- Compute lcm(p - 1, q - 1)

- Compute d = e-1

mod lcm(p - 1, q - 1)

- We always take e = 65537 here

- Check that d is ‘large enough’, if not, start over

Here, ‘large enough’ for d means large enough to prevent methods like Wiener’s attack or the Boneh-Durfree attack from recovering the private key. The latter attack works for d < n0.292 , so for safety, NIST SP 800-56B–necessary for FIPS certification–requires that d should be at least half the RSA size in bits.

To convert the above to CRT, we now have to add steps for computing our additional values. We also move our computation of n to the end to allow use of rsa_n as an additional working buffer when computing dp and dq; this has the nice side effect of shaving a few cycles when d isn’t sufficiently large the first time.

- Generate random primes p and q

Compute n = p * q- Compute (p - 1) * (q - 1)

- Compute d = e-1 mod lcm(p - 1, q - 1)

- We always take e = 65537 here

- Check that d is ‘large enough’, if not, start over

- Compute dp = d mod p - 1

- Compute dq = d mod q - 1

- Compute qinv = q-1 mod p

- Compute n = p * q

The computation of dp and dq are straightforward, but computing modular inverses can be tricky to do securely. One thing to watch out for is that the runtime of the modular inverse doesn’t depend on the inputs; otherwise, an attacker could time how long the algorithm takes to run, and leak bits of the key. While this sounds highly theoretical, it was actually the basis of the recent EUCLEAK attack which allows unauthorized cloning of smartcards and FIDO keys.

In our implementation, we make use of the constant-time binary extended Euclidean algorithm (EEA) from BoringSSL, as formally verified by David Benjamin in the fiat-crypto project. Rather than try to perform long division each step like in the typical extended Euclidean algorithm, this binary EEA shuffles intermediate values around to only require division by two, which can be performed with a simple bit shift.

Like the traditional EEA, however, the binary EEA does require a lot of memory. For everything to fit properly in dmem, we make extensive use of not-in-use buffers as scratch space for computations. For instance, when computing qInv with the EEA, we use all of tmp_scratchpad, rsa_d, and rsa_cofactor for a cumulative 1.25 KiB of scratch space.

As a last wistful note, the particularly keen reader might wonder whether we could get away without computing d = e-1 mod lcm(p - 1, q - 1); after all, we immediately reduce it mod p - 1 and q - 1, so it should suffice to compute dp = e-1 mod p - 1 and dq = e-1 mod q - 1 directly.

While this would be a nice trick, we do need to check that d is sufficiently large as part of FIPS compliance, and there’s no practical way short of computing d to determine this. The CRT does guarantee that given d mod p - 1 = dp and d mod q - 1 = dq we can recover a unique d modulo lcm(p - 1, q - 1); this is left as an exercise to the reader (hint: apply CRT to p - 1 and (q - 1) / gcd(p - 1, q - 1)) and suggests the following possible approach:

- …

- Compute dp = e-1 mod p - 1

- Compute dq = e-1 mod q - 1

- Compute k = (q - 1) / gcd(p - 1, q - 1)

- Recover d from dp, dq mod k

- Check that d is ‘large enough’

- …

but to our knowledge this hasn’t shown up in practice, as it’s more than likely the overhead from the computation of k and CRT reconstruction outweighs any benefits.

CRT Modular Exponentiation (or, Working with Too Few Registers)

When running the CRT modexp, we expand from a simple call to the square-and-multiply routine to the following:

- Compute mp = m mod p

- Compute cp = (mp)^(dp) mod p (square-and-multiply)

- Compute mq = m mod q

- Compute cq = (mq)^(dq) mod q (square-and-multiply)

- Compute c = q * ((cp - cq mod p) * qinv mod p) + cq

While this looks like a fairly straightforward series of operations, first note that we’ve rearranged mq to only be computed once cp is complete; this is because we don’t have sufficient memory to store mq across the first square-and-multiply call. In fact, the result of the modular exponent overwrites the buffer storing of dp, as we need every other bit of buffer space to compute cq after and dp isn’t used again.

Fortunately, once we reach the CRT reconstruction step, a number of buffers free up for use. Things become fairly straightforward, and we use a simple conditional addition and binary long division for the last two reductions mod p. (We certainly could modify the square-and-multiply function to output cp and cq in Montgomery form, but for simplicity we simply do these last two operations outside the Montgomery domain.)

Memory space isn’t the only limited resource when writing assembly for embedded targets like this cryptographic accelerator; the other difficulty can be running out of available registers.

The accelerator has 32 32-bit general purpose registers available, and when running the existing modexp routine, 20+ of those get overwritten with working values. On top of this, the CRT modexp routine needs to take in 12 input registers containing pointers to memory for output. At first glance, this seems to be a hopeless situation: we don’t have enough registers for inputs and working values together.

This is a situation that compilers run into frequently. When you compile a program from a higher-level language and the number of registers needed approaches the number of total registers, it can be difficult to assign values to registers in a way that keeps the values around for long enough. This phenomenon is called “register pressure,” and the process of assigning values to registers is called “register allocation”; higher register pressure makes register allocation difficult to impossible.

To address this, compilers will typically handle high register pressure with “spilling,” where the compiler inserts instructions to stash some register values in memory, loading the values back into registers once they’re needed. This isn’t ideal though, as it incurs a performance penalty and may expose sensitive values if attackers can snoop on the memory bus.

Fortunately, when hand-writing assembly, one can often avoid spilling to memory by a bit of register gymnastics. By shuffling values out of registers which get overwritten (or “clobbered”) before a section of code, and then restoring them as needed, we can get the correct values where we need them without incurring a significant performance hit.

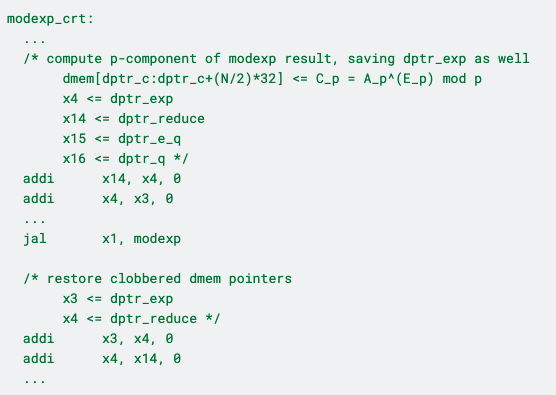

As an example, here’s where we compute cp = c mod p by calling the pre-existing square-and-multiply algorithm:

Here’s the same routine in pseudocode, for simplicity:

Copy register x4 -> x14

Copy register x3 -> x4

…

Call square-and-multiply routine

Copy register x4 -> x3

Copy register x14 -> x4

Here, the register x14 is used as an input to modexp containing the pointers to the base, exponent, and modulus respectively. x3 and x4 contain pointers to important working buffers, and modexp clobbers 20+ registers, including x3.

At this point in the program, there aren’t any remaining registers which are left over to hold the value in x3. Fortunately, modexp doesn’t overwrite the input register x14, so we can actually use x4 as storage, retrieving its value after the function call. In other words, we shuffle

x14 <= x4 <= x3,

call the buffer, and then shuffle back the values as

x3 <= x4 <= x14

restoring x3 and x4 in a situation where it looked like we were out of registers. Because the register pressure is so high throughout the bulk of the modular exponentiation routine, this required precise attention to exactly how registers could be rearranged to avoid spilling.

Security and Maintenance Considerations (or, Working with Too Many Details)

To keep such code maintainable as well as performant, we carefully document the values stored in each register throughout the code, and at the top of each method maintain

a list of input and output registers, including buffer sizes

a list of all registers clobbered by the routine

a list of all CPU flags potentially overwritten

as well as any additional function-specific details needed by a caller. For instance, at the top of the modular inversion routine used to compute qinv = q-1 mod p, we have the following doc comment:

which informs a caller that any values in registers x2 to x6, x31, or w20 to w26 should be moved elsewhere before calling. Part of maintaining assembly for a cryptographic coprocessor (and frankly, any cryptographic code!) is meticulously ensuring that documentation like this is kept up to date. One future task we’d like to tackle is adding further linting checks to ensure such information keeps in sync with the code.

Automated checks can be invaluable in developing software, especially when security is a concern. As an example, a basic mechanism was built into the legacy codebase for verifying that a provided function is constant time, guaranteeing safety from simple timing attacks.

One approach to check whether a function is constant time is to run it on a bunch of random inputs and compare the number of clock cycles each time. While this can be useful for proving a function isn’t constant time, it can’t prove a function is constant time unless it ends up trying every single possible input. Instead, the aforementioned mechanism doesn’t run the code at all: it scans the assembly itself and builds out a graph of the control flow of the program, inspecting what makes the program flow from one node to the next.

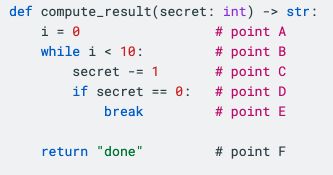

As an example, a toy Python program like

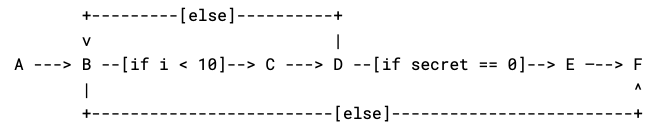

would have a control flow graph of

Each point in this graph is a commented point in the program above, and each edge is a part of the program that could run next. If there’s multiple places a program could go (e.g. an if statement), we label the edge with the condition for it being taken.

By inspecting this graph, we can see that there is one edge that depends on the secret value we provide our function. This corresponds to the if secret == 0: break part of the program, where we exit the loop early if our secret value becomes 0. Indeed, if our secret value is any integer from 1 to 10, then the loop will exit early and an attacker timing the function would be able to detect this. The constant-time check script uses this principle to show that functions are constant time as part of the standard test suite. To allow testing alongside all the other crypto tests, a otbn_consttime_test Bazel rule allows for detailing exactly which routines and sensitive values to trace on every test suite run.

Conclusion

Cryptography can be delightfully infuriating in the way that a cryptosystem expressed in just a few lines of math can require thousands of lines of careful, reasoned code changes to implement properly. Details like performance, maintainability, side channel protections, backwards compatibility, memory and register limitations, and testing implications all must be front-of-mind for the engineer when implementing these systems.

Fortunately, with a combination of careful resource utilization, detailed documentation, clever tooling, and a bit of perseverance, we can find ways to sustainably squeeze out additional performance in even the most resource-constrained systems.

If you’re interested in learning more about our approach to maintainable cryptography, or how ZeroRISC is democratizing access to secure silicon, sign up for our early-access program or drop us a line at info@zerorisc.com.