Fast, Flexible, Future-Proof: The “Cryptolib” Embedded Cryptography Library

This post describes design choices we made in developing the cryptolib embedded cryptographic library. Initially developed for OpenTitan, we have added support for upcoming accelerators while maintaining backward compatibility. This post explores how we balanced performance, flexibility, and maintainability, while also highlighting the importance of key development practices like hardware/software co-design.

This library represents countless hours of engineering effort over many years and is the culmination of a series of careful engineering choices designed to serve both developers and integrators for the long-term. We have emphasized modularity and configurability such that it can be flexibly implemented across a variety of devices, aligned with the open-source mentality of reuse and adaptation.

Cryptolib: Cryptography for the Real-World

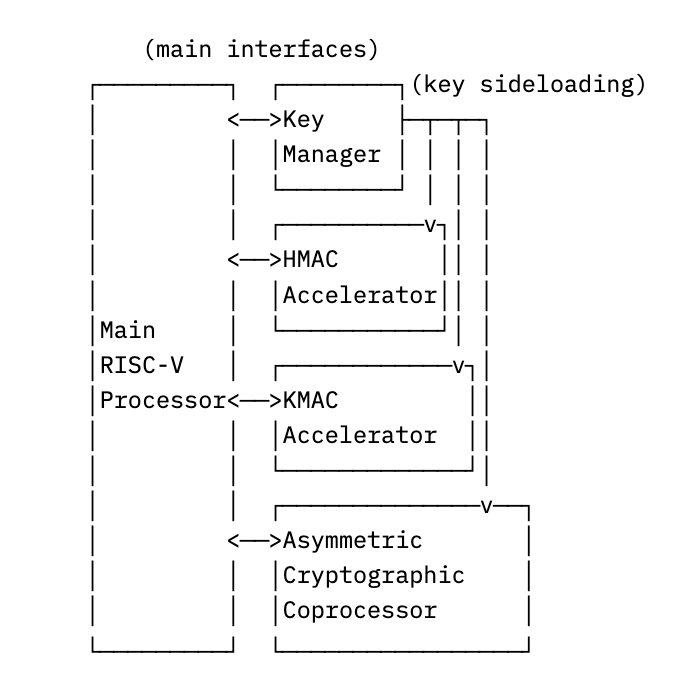

Cryptolib is the cryptographic library paired to our OpenTitan IP-based set of hardware cryptographic accelerators. Many configurations have a standard RISC-V processor, but also

a hardware key manager, for securely storing keys

hardware accelerators for symmetric operations like AES encryption

and a cryptography coprocessor for asymmetric operations like RSA signatures.

Together, this roughly looks like:

In order to make use of all of the above hardware, cryptolib itself consists of a combination of

Drivers, for controlling each key manager and each hardware accelerator

Coprocessor Assembly, for implementing algorithms on the asymmetric cryptography coprocessor

Main Processor Code, for initializing operations on each accelerator, as well as performing some hardened cryptographic operations (i.e. GHASH for AES-GCM)

As an example of what this looks like in practice, let’s trace what happens when a user requests a single RSA signature.

[Application Code] The code on the main RISC-V processor makes a call to the synchronous cryptolib API, e.g. using otcrypto_rsa_sign, providing the message and appropriate private key for signing

[Cryptolib API] The cryptolib implementation of otcrypto_rsa_sign loads the “RSA sign” program onto the cryptographic coprocessor and copies the provided message and key into the coprocessor memory

[Cryptolib Driver] The cryptographic coprocessor driver triggers the coprocessor to start performing the signature operation

[Cryptolib Coprocessor Implementation] The coprocessor performs the signature and informs the processor of completion

[Return] The processor fetches the signature from coprocessor memory, clears the coprocessor memory, and returns the signature back to the API caller

(Note that while the above directly passes key material to cryptolib for signing, keys can instead be kept in the hardware key manager for increased security, where the coprocessor can fetch them via sideloading.)

In terms of algorithms, cryptolib presently includes support for

AES-128, AES-192, and AES-256 in ECB, CBC, CFB, CTR, OFB, and GCM modes

SHA2-256, SHA2-384, and SHA2-512

SHA3-224, SHA3-256, SHA3-384, and SHA3-512

SHAKE128, SHAKE256, cSHAKE128, and cSHAKE256

HMAC with SHA2-256, SHA2-384, or SHA2-512

KMAC128 and KMAC256

RSA-2048, RSA-3072, and RSA-4096 key generation

RSA-2048, RSA-3072, and RSA-4096 PKCS v1.5 signatures

RSA-2048, RSA-3072, and RSA-4096 PSS signatures

RSA-2048, RSA-3072, and RSA-4096 OAEP encryption

ECDSA with NIST P-256 and NIST P-384 curves

ECDH with NIST P-256 and NIST P-384 curves

Ed25519

X25519

AES-CTR-DRBG with or without a hardware TRNG

HMAC-KDF-CTR

HKDF

and KMAC-KDF.

While extensive, cryptolib has been architected in a way that allows choosing the algorithms you choose to support, allowing it to remain small while usable in a variety of contexts. We’ll discuss this point in detail later.

Lastly, cryptolib also includes a number of features for maintainability, including

A detailed suite of functional test integrated into ZeroRISC’s hardware CI platform

Automated KAT testing against both Wycheproof and NIST CAVP vectors

An extensive simulation and debugging toolchain for the ACC

and more.

To dive into how we maintain such an extensive library, we’ll start with the most exciting part: performance.

Performance: Accelerators, Simulation, and Optimizations

In order to deliver high-performance cryptography, cryptolib takes a heterogeneous approach to acceleration:

Symmetric cryptography like AES encryption often requires high throughput, and implementations are unlikely to change over time, meaning that it’s a good fit for a dedicated hardware accelerator

Asymmetric cryptography like ECDSA can be optimized in clever ways and needs more attention to prevent side-channel leakage, meaning a programmable accelerator makes sense

For symmetric operations handled by dedicated accelerators, traditional hardware cryptography tricks ensure high throughput, though some more recent techniques–such as Domain-Oriented Masking–are critical in mitigating side-channel leakage while maintaining good performance.

In terms of cryptolib, however, such operations are fairly straightforward: the implementation for the RISC-V processor simply loads the appropriate values into the appropriate MMIO (memory-mapped input/output) registers, triggers the operation, and fetches the results upon completion. For instance, the cryptolib AES driver:

Ensures that the AES accelerator has access to entropy for masking, via a MMIO read

Writes the following into AES accelerator MMIO registers:

whether to encrypt/decrypt

whether to use a sideloaded key

the cipher mode

the AES key to use

and the initialization vector to use

Alternately (1) reads ciphertext blocks out from the accelerator and (2) writes new plaintext blocks to the accelerator as provided through the cryptolib API, also via MMIO

Reads the IV back to confirm it hasn’t changed, and clears the AES accelerator internal state via a MMIO write

More interesting are cryptolib’s implementations of asymmetric operations, where the code loaded onto the cryptographic coprocessor can undergo significant optimization. For an in-depth analysis of a large optimization with ~3x performance gain, see Part 1 and Part 2 of our recent exposition on optimizing RSA using Chinese remainder theorem modular exponentiation.

As a self-contained example of making cryptolib performant, we can review our Ed25519 elliptic curve signature implementation for the cryptographic coprocessor. Algorithms such as Ed25519 are defined by a set of immutable steps that any implementation has to follow, so at first glance, it might not seem like there’s much room to optimize. For instance, Ed25519 dictates that a signer must:

Compute a SHA-512 hash on their private key and split the result in half

Multiply an elliptic curve point by the first half to get the public key

Compute a SHA-512 of the second half concatenated with the message

Multiply an elliptic curve point by the result

Compute a SHA-512 the output of that with the public key and the message

etc.

Most of the room for improving performance instead comes from how these base operations, such as hashing or elliptic curve point multiplication, are implemented. We’ll start with hashing: given what we know about the Ed25519 implementation, we might consider something like the following:

Have the main processor delegate as many SHA-512 operations as possible to a hardware accelerator before needing to perform an elliptic curve operation

Have the main processor take the results and load them into the cryptographic coprocessor, which will perform as many of the elliptic curve operations as possible on the results

Have the main processor take those results and perform what SHA-512 hashes are needed

etc.

While this seems like a straightforward approach, it adds a remarkable amount of overhead by requiring constant data movement through the processor as well as starting and stopping the cryptographic coprocessor. Additionally, this approach makes for a more complex security analysis, as various intermediate values from the operation travel across internal buses when computing a signature.

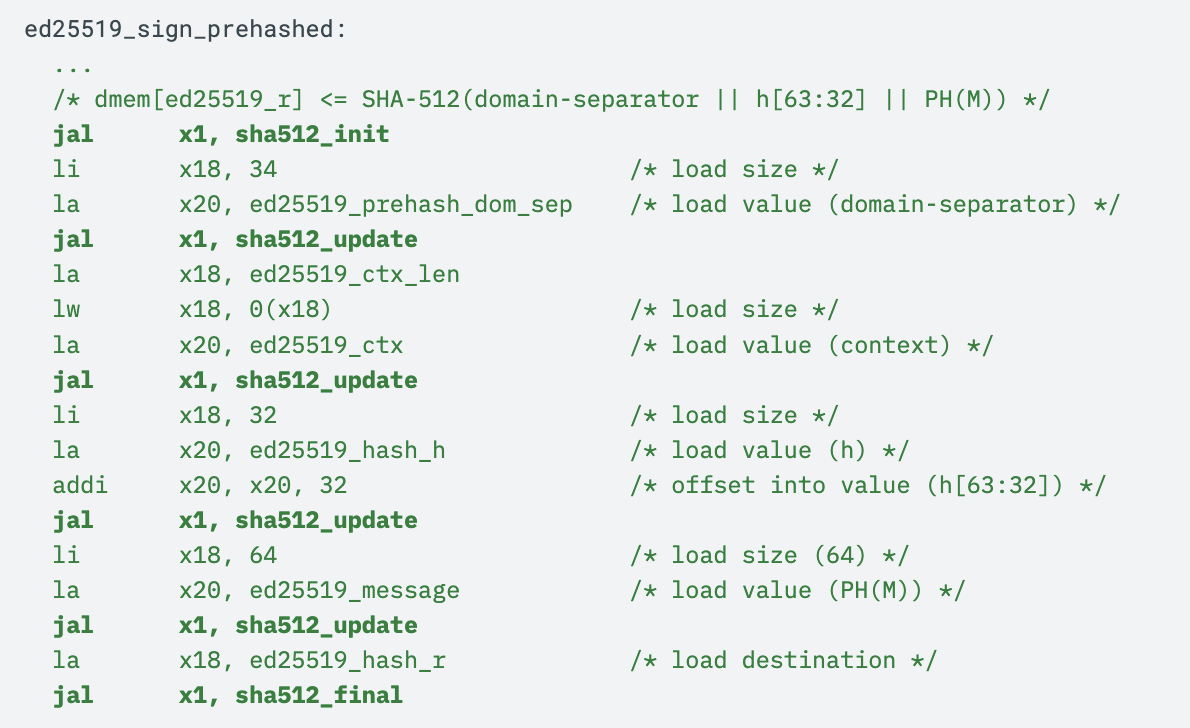

Instead, we might consider implementing a SHA-512 implementation in the cryptographic coprocessor itself. While it may not have the throughput of the dedicated hardware accelerator, it has low enough latency to make it the better approach for Ed25519 signing: see here for our internal implementation, which makes extensive use of wide register operations to efficiently manage SHA-512 lanes while minimizing code size.

Now, rather than now having to call back to the main processor, SHA-512 hashes can be computed using function calls to sha512_init, sha512_update, and sha512_final as follows, with all state maintained within the coprocessor:

As for the elliptic curve operations, these offer even more room for optimization, down to the arithmetic level. Since the logic of Ed25519 requires multiple elliptic curve operations, and each elliptic curve operation in turn requires many arithmetic operations, shaving even a few cycles off these base operations can result in remarkable speedups.

For instance, one frequently-used core operation is multiplication mod p, where p is the Ed25519 prime 2^255 - 19. Naively, one could simply multiply two 255-bit numbers together, and then use long division to get the remainder mod p, but in practice this is fairly slow. Faster modular reduction tricks, such as Barrett reduction, do exist and are necessary at points, see our implementation for the Ed25519 scalar field here.

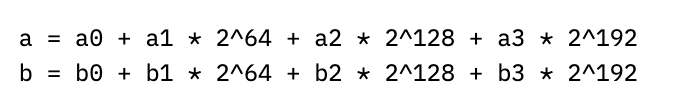

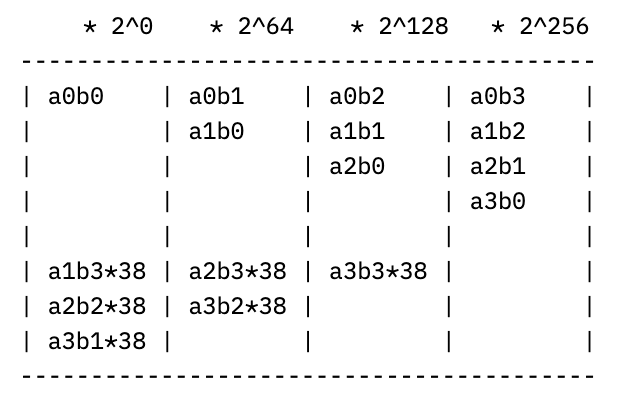

But we can do even better than that by realizing that p = 2^255 - 19 is so close to a power of two (for the mathematicians, a pseudo-Mersenne prime). Pretend we have two numbers a and b mod p, which we can split into four 64-bit chunks:

If we multiply out a times b, we’ll get

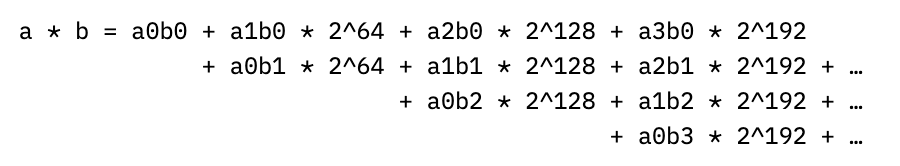

where the ellipses contain terms multiplied by 2^256 and higher. Since we want to work mod p though, we can note that 2^256 mod p = 38, so that e.g. a1b3 * 2^256 “wraps around” and just becomes 38*a1b3. If we continue this “wrapping around” process by reducing each power of 2 mod p, the columns of coefficients above start to look like (with multiplier on top of each column):

meaning we can just compute these smaller, 64-bit partial products instead, an operation which the coprocessor has dedicated instructions for. While this will work as-is–computing each partial sum, adding them together, and then addressing the carry-out from the last column–we can do even better by eagerly addressing this last part.

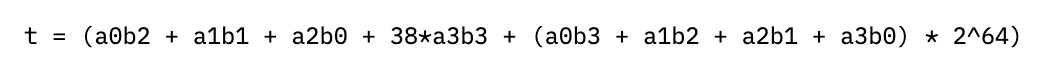

Rather than addressing the carry-out last, we can pre-compute the partial sums of the right two columns, wrapping around the result and adding it to the left two columns. This looks like computing a new value for the right two columns

which splits into four 64-bit chunks t0-t3 as before, resulting in the updated columns of:

allowing the results in the left and right columns to be added at the end with a single conditional subtraction of p. Making strong use of the cryptographic coprocessor’s instructions for wide register shifts and computing 64-bit partial products, this allows for modular multiplication in a mere 24 cycles, significantly speeding up the elliptic curve operations built on top of it. For comparison, the Barrett reduction we use for the scalar field takes 73 cycles per modular multiplication, and a generic constant-time bignum division that is not specialized to the divisor takes about 15,000 cycles for 256-bit operands. These saved cycles truly count; the modular multiplication is called about 7,000 times per signature. If we used Barrett reduction for the coordinate field, then the entire signature routine would be more than 2x slower.

Of course, when implementing such complex optimized routines, especially in assembly, the risk of implementation mistakes goes up. Especially for modular reduction routines, some instructions are no-ops except in very specific cases, so it is easy to omit them or miss bugs (arithmetic bugs like this have been found, among other places, in modular reductions from well-established cryptographic libraries like openssl, go/crypto and TweetNaCl). To ensure functional correctness, we rely on techniques beyond testing for critical and complex routines like this one. We implemented a full model of the coprocessor within the proof assistant Rocq and verified the exact code for 25519 modular reduction in fact computes modular reduction for all inputs. Formal tools like Rocq allow us to cover the entire cryptographically-large input space for high-risk routines like this, rather than relying on luck to hit rare cases in random testing. Our P-256 modular reduction is also verified against an ad-hoc earlier prototype of the coprocessor model, and the Ed25519 scalar reduction is verified at an algorithmic level (these other proofs predate the updated model and are not yet ported).

By using techniques like these which carefully leverage the instruction set of the coprocessor, as well as employing techniques such as hardware/software co-design (more on this in a future post), we can provide highly performant cryptographic implementations with no cost to flexibility or maintainability.

Flexibility: Modular Design and Testing

While performance is exciting, it’s worth little if the implementation in question won’t work for your application. Embedded cryptography is a critical component in devices of all scales, from the smallest secure element to a fully-featured baseboard management controller in high-end servers. Each application comes with different kinds of onboard hardware, available memory, and requirements in terms of algorithms and their performance.

Rather than try to write a bespoke, separately-verified cryptographic library for every possible device, our aim with cryptolib is to allow for easy tailoring to a myriad of different possible configurations. As part of this effort, we’ve put careful work into separating out different cryptographic APIs to allow easy customization for any deployment.

For instance, if an application only called for ECDSA P-384 for firmware signatures and TLS v1.3 with the TLS_ECDHE_ECDSA_WITH_AES_256_GCM_SHA384 ciphersuite, then ideally one would only want

Dedicated hardware accelerators for AES and SHA-384

A cryptographic coprocessor with programs for P-384 ECDSA and ECDH

Drivers and APIs for both accelerators and the coprocessor

as anything else would just waste die area or storage. By carefully putting effort into modularizing cryptolib, e.g. by separating out the SHA2 and SHA3 APIs, we ensure cryptolib can be flexibly configured by integrators who select exactly which parts of the cryptographic hardware and cryptolib they need for their application, letting them reap all of the benefits of a single carefully-maintained cryptographic library while also providing an end-product that works with their constraints.

As part of making this single cryptolib useful in any configuration, the testing suite is similarly modularized, allowing for easy regression testing of any integration. Additionally, we’ve put extensive effort into maintaining a test framework to run both NIST CAVP and Wycheproof known answer tests (KATs), easing certification for integrators and allowing them to maintain confidence of correctness. For instance, after we performed the RSA CRT optimization, we put extensive effort into ensuring that everything passed the appropriate RSA KATs to be confident our optimizations were correct.

By keeping the design modular and continuously verifying implementations against a wide suite of functional tests and KATs, we’re able to keep cryptolib ready to distribute with confidence in any number of applications.

Maintainability: Tooling, CI, and Documentation

The last pillar of our cryptolib strategy to highlight is maintainability, as keeping a maintainable code base is essential to any auditing, certification, or further optimization effort.

A large part of keeping software maintainable is catching problems early. Alongside the functional tests and KATs which we check in both on-push and weekly CI jobs, cryptolib contains a wide array of additional tooling for the cryptographic coprocessor, from a full cycle-accurate simulator to detailed static analysis tooling, e.g. for ensuring the code is still constant time after each change.

One excellent example of static analysis tooling providing maintainability comes from our process of checking cycle counts. When defending against fault injection, one trick that can be helpful is to count the number of cycles an operation should have taken and compare it against how many it actually took. Unfortunately, the expected cycle count for a program can sometimes be a range of possible cycle counts, and the upper and lower bounds can take a bit of manual labor to compute.

Rather than manually maintaining this range, we instead put a significant effort into static analysis tooling to compute these ranges for us, inserting them at build-time into auto-generated C headers which cryptolib uses to check cycle counts after coprocessor operations.

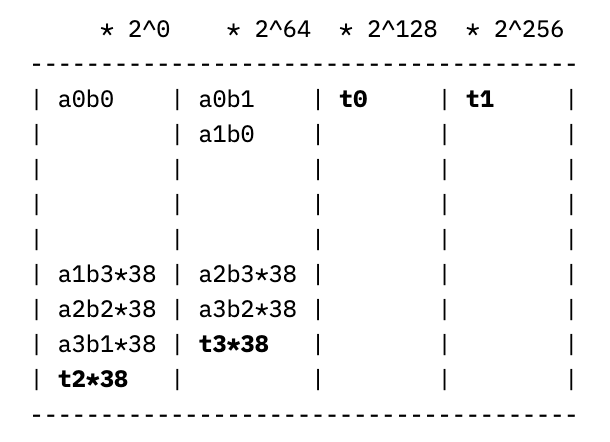

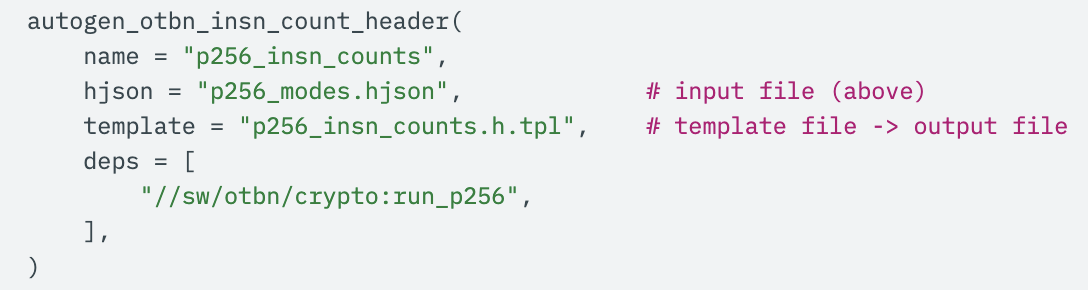

To set this up, all that’s needed is a simple HJSON file containing the assembly labels corresponding to different “modes” that the coprocessor can be launched in, e.g. for keygen/signing/verifying:

Note that you can also exclude failure control paths, such as those going through the label p256_invalid_input: the static analysis tool will automatically prune these during its pass.

From there, a single Bazel rule results in the autogenerated C header, complete with ranges of possible instruction counts: merely adding

along with a basic header template is all it takes. Underneath the hood, a full static analysis script parses the generated run_p256 top-level P-256 ECC executable, tracing the control flow graph and using various tricks from compiler design to efficiently propagate instruction count bounds through the end of the program.

From there, checking the instruction count is trivial; by adding a simple macro to the coprocessor driver we can–with just one line of C added!–mitigate fault injection attacks via automatically checking the instruction count against the possible cycle count ranges derived at build-time, even for routines that are not constant-time. Tooling like this allows developers and downstream integrators to work efficiently and focus on delivering a secure, performant product.

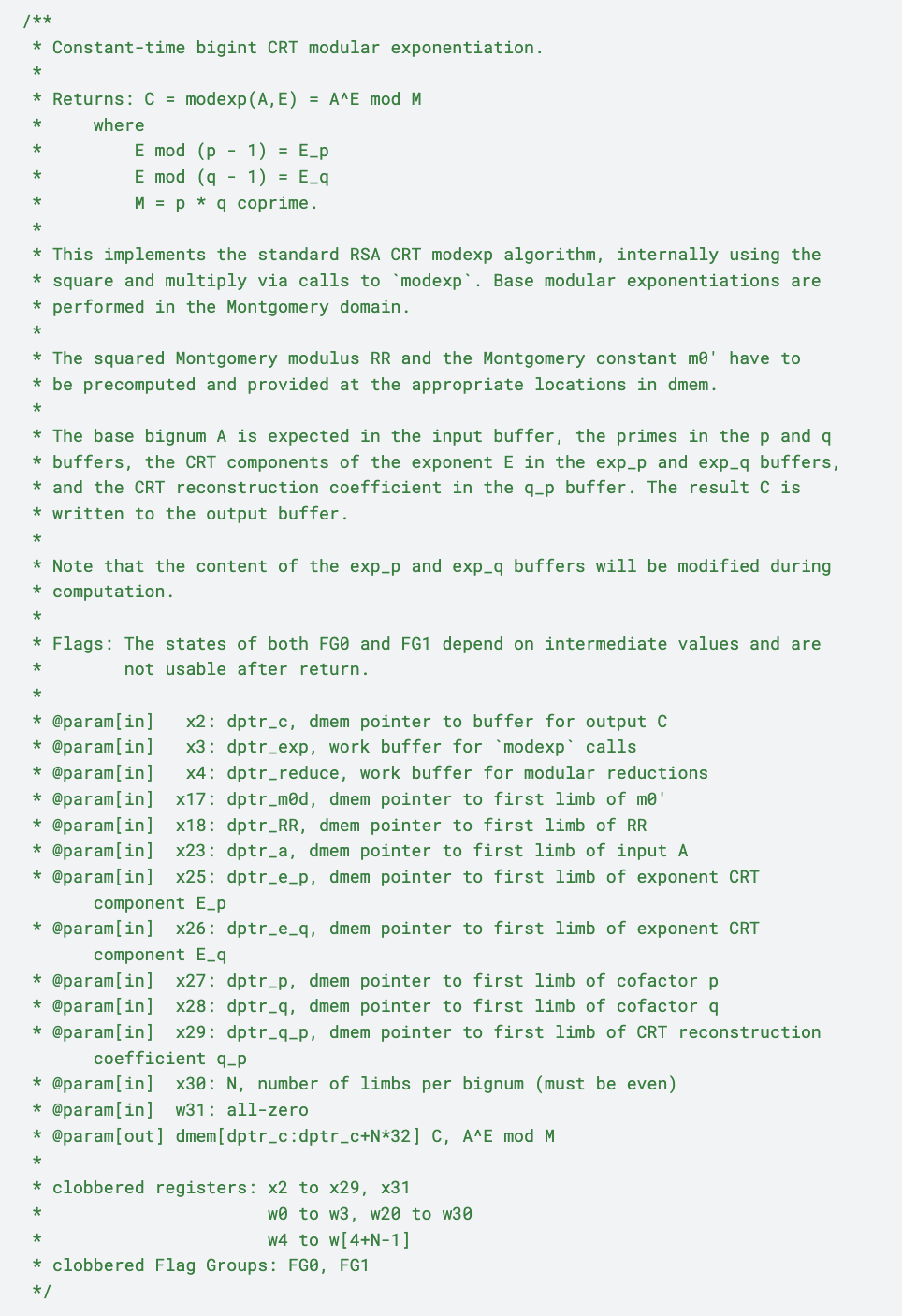

As a last note regarding maintainability, cryptolib is designed to prioritize documentation first. Docs are automatically generated for the cryptolib API with full descriptions of each operation, and we have placed heavy emphasis in the code on ensuring that all optimizations and design choices are well-documented for future developers. Assembly for the cryptography coprocessor is documented not only with input and output registers for each operation, but also with detailed descriptions of side-effects, usage details, and exactly which registers and flag groups are clobbered. As an example, our RSA modular multiplication routine is documented with all of the following:

These details are invaluable when working on the coprocessor assembly, as cryptographic engineers often have to balance thinking on at several levels at once: the mathematical level where the cryptography takes place, the implementation level where such operations are reduced to algorithms, and the machinic level at which those algorithms become individual instructions. While these may seem like discrete, separable layers, real-world cryptographic implementations can lead to deeply-ingrained interactions between all three. For instance, hardware constraints can affect which algorithm-level approaches are viable, and the small changes in the choice of e.g. a finite field modulus can wildly change what arithmetic looks like at the instruction-level.

In this sense, cryptographic engineering is rhizomatic: its ‘layers’ don’t form a simple stack, but are inextricably, densely linked together. This makes for a significant cognitive load, and easing it with clear documentation can prevent mistakes before they happen while reducing the effort it takes to deliver a high-assurance cryptographic library.

In the future, we plan to automatedly check this metadata via build-time scripts, providing the user with a warning when the clobbered registers/flag groups are out of sync with the code, or when a caller attempts to use the value in a register clobbered by a callee. With thoughtful efforts like these, we aim to ensure even highly-optimized routines remain workable indefinitely.

Conclusion: Cryptolib as a Source of Best Practice

Cryptolib as an embedded cryptography library has been built from the ground up with performance, flexibility, and maintainability at the forefront.

By simultaneously prioritizing these features through continuous effort and engineering expertise, we open the possibility of a high-assurance cryptographic library that not only adapts fluidly to new integrations while providing excellent performance, but also ensures that long-term maintenance and certification efforts are reasonable.

This means that the same cryptographic library can run on RoTs from those in the smallest IoT devices to the largest server baseboards, all while providing a smooth experience for developers and integrators.

If you’re interested in learning more about our approach to maintainable, production-grade cryptography, or hearing about ZeroRISC in general, sign up for our early-access program or reach out at info@zerorisc.com.