RSA with CRT Part 1: Speed up RSA by 3x with This One Simple Trick

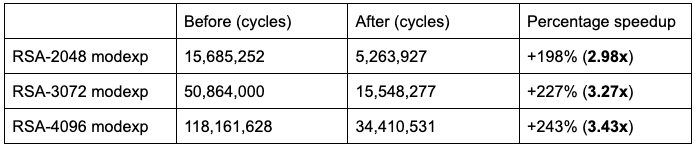

This post is the first of a two-part series describing recent improvements to make our embedded RSA software (originally developed in the OpenTitan codebase) production ready, leading to a huge speedup for core operations:

Note: This is the full-length modular exponentiation that forms the core of signing and decryption operations in the RSA cryptosystem. Top-level speedups for signing and decryption are similar.

In this post, we’ll go over the mathematical basis for this standard optimization. In the second part, we’ll go deeper into implementation details and share what a major, specialized, pure-assembly code change looks like in practice.

The Chinese Remainder Theorem

The technique used is ancient, originating in the 3rd century work of mathematician Sun Zi, with a complete theorem dating back to 1247. It states that, if a set of integer moduli n0…nk-1 is pairwise coprime (meaning that the GCD of any pair is 1), then any set of residues a0…ak-1 from those moduli has a solution x such that x is equivalent to every ai modulo ni, and furthermore that the solution x is unique modulo N = n0 * … * nk-1.

This theorem enables us to translate a problem modulo N into a problem modulo factors of N, without introducing ambiguity or multiple solutions. Operations like multiplication modulo large numbers scale more than linearly with the bit-length of the modulus, so doing an operation twice modulo two half-size factors is significantly faster than doing the same operation once with one full-sized value. This is the fundamental property we used to speed up RSA – a standard technique today, but non-trivial to implement in new cryptographic libraries.

The RSA Cryptosystem

RSA was first described in 1977 and is one of the first cryptographic schemes that could operate using separate public and private keys (as opposed to requiring that the people communicating with each other have a previously shared secret key). It’s one of the oldest algorithms that’s still considered secure and in widespread use, whose remarkable endurance can be attributed to its elegant mathematical simplicity.

The core of the algorithm fits in just a few lines (eliding a couple of details, see IETF RFC 8017 for a more formal and authoritative description):

- Choose a fixed, public exponent e. It can be anything, but popular choices for efficiency include 3 and 65537.

- Randomly generate two prime numbers p and q. Their product, n = p * q, combined with the exponent e, is your public key. The bit-length of n determines the “RSA size”; RSA-2048 means that p and q are 1024 bits each and n is 2048 bits.

- Compute the inverse of e modulo lcm(p - 1, q - 1); that is, find a number d such that e * d mod lcm(p - 1, q - 1) = 1. This integer, d, is your private key. Without knowing p and q, it’s not feasible for someone else to compute it.

- To encrypt a message, add padding according to your chosen scheme (e.g.OAEP) to get an integer m representing the message, and compute the ciphertext c = me mod n.

- To decrypt the message, the recipient computes m = cd mod n.

This works because (me)d mod n = med mod n, and ed mod lcm(p - 1, q - 1) = 1. Therefore, med is congruent to mk * lcm(p - 1, q - 1) + 1 modulo n, p, and q. By Fermat’s Little Theorem, we know that since p and q are prime, any number raised to a multiple of (p-1) is equivalent to 1 modulo p, and similarly any number raised to a multiple of (q-1) is equivalent to 1 modulo q. We can therefore cancel out the k * lcm(p - 1, q - 1) factor of the exponent both modulo p and modulo q, and conclude that med is equivalent to m modulo p and also modulo q. By the Chinese Remainder Theorem (hello again!) we know that this means med mod n = m, the original message.

This scheme works for signatures too. An RSA signature uses the same underlying modular operations as encryption; to sign a message, the signer creates a signature s = md mod n and the verifier checks it by computing se mod n and checking that the result is equivalent to the message. Essentially, signing uses the same operation as decryption, and verifying uses the same operation as encryption.

Of the RSA operations:

Encryption and verification (exponentiation with e) is generally very fast, since e is public and small.

Signing and decryption (exponentiation with d) are usually much slower, since d is large and must be kept secret.

Key generation is usually extremely slow compared to either of these, and especially compared to more modern public-key schemes based on elliptic curves. Picking random primes is not easy!

RSA with CRT

The above description of RSA is mathematically accurate, and it’s what our initial implementation in the prior codebase computed. However, if you look at RFC 8017 or most performant RSA implementations, you’ll see a lot of references to “CRT” and numbers like dp and dq that don’t appear here. This is because most production-quality implementations use the Chinese Remainder Theorem (CRT) to translate expensive RSA operations mod N into operations modulo p and q.

Here, we’ll dive into the high-level mathematical description of implementing RSA with CRT. In the next blog post, we’ll describe implementing each part of this description on an asymmetric cryptography acceleration, the critical part of a hardware root of trust which handles performing cryptography such as RSA.

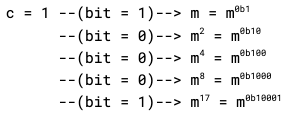

First, let’s review how one might directly compute an RSA signature, i.e. calculate c = md mod n. The standard approach is the “square-and-multiply” algorithm, which reads the binary representation of d bit by bit to compute md mod n. Here’s what it looks like in practice:

- Start with c = 1.

- Read out each bit of the exponent d, left to right:

- If the bit is 0, replace c with c2 mod n

- If the bit is 1, replace c with c2 * m mod n

To see why this works, take d = 17. In binary, d = 0b10001. Reading the bits of d left to right, our result becomes (dropping the “mod n” in each line for clarity)

Every time we see a ‘0’, we square our result, which doubles the exponent, which in turn puts a binary ‘0’ on the end of the exponent. Every time we see a ‘1’, we square our result and multiply by m, which doubles and adds one to the exponent, putting a binary ‘1’ there instead. Bit by bit, we build out our exponent.

While this modular exponentiation (or “modexp”) algorithm is perfectly functional, its runtime scales by the cube of the bitlength of its inputs. As such, we’d rather make use of this modexp algorithm mod p and mod q, instead of mod n.

Here’s what a divide and conquer RSA with CRT approach might look like instead:

- [Divide] Compute mp = m mod p and mq = m mod q

- [Conquer] Calculate cp = (mp)d mod p and cq = (mq)d mod q (using square-and-multiply)

- [Reconstruct] Use cp and cq to recover the unique c where c mod p = cp and c mod q = cq

This will certainly speed things up, but we can do even better. Recall that by Fermat’s Little Theorem, any number raised to the power of (p-1) mod p is equivalent to 1 mod p. This means that, if we write d as d = (d mod (p - 1)) + k(p - 1) for some k, we can just cancel out the k(p - 1) when performing our modexp. This means we can rewrite the algorithm as

- …

- [Conquer] Calculate cp = (mp)d mod (p - 1) mod p and cq = (mq)d mod (q - 1) mod q

- …

which halves the time it takes to compute cp and cq with our square-and-multiply algorithm, since there are now half as many bits in our exponent.

To complete our RSA CRT algorithm, let’s think about how we’d actually implement each step. The first step, labeled “[Divide]” above, can be done using simple modular reduction: we can just perform long division and take the remainder. The ‘conquer’ step can be done using our square-and-multiply algorithm. What about the reconstruction step? The CRT guarantees us a unique c with c mod p = cp and c mod q = cq, but it doesn’t provide us an explicit way to recover that c.

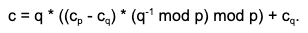

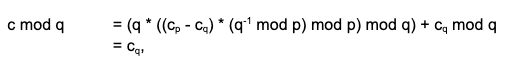

Fortunately, there is an explicit formula we can use: Garner’s formula. Given cp and cq, we can recover c as

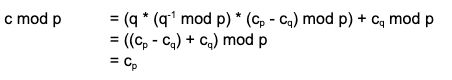

To see why this formula works, we manually compute

and

just as we hoped.

While most of this formula is addition and multiplication mod q, there is the need to compute q-1 mod p, which is a bit more expensive. Fortunately, this value doesn’t depend on our base or exponent, just the cofactors of n, so we can precompute it along with dp = d mod (p - 1) and dq = d mod (q - 1) when we generate our RSA keys.

At last, our complete version of the RSA CRT modexp algorithm is (changes in bold):

- [Preconditions] Assume we’ve already precomputed dp = d mod (p - 1), dq = d mod (q - 1), and qinv = q -1 mod p.

- [Divide] Compute mp = m mod p and mq = m mod q

- [Conquer] Calculate cp = (mp )^(dp) mod p and cq = (mq )^(dq) mod q, using the square-and-multiply algorithm

- [Reconstruct] Recover c = q * ((cp- cq ) * qinv mod p) + cq as the result

For a performance estimate, we note that the runtime in practice is dominated by the two modular exponentiations in the ‘conquer’ step. Since p and q are half the size of n, the two modexp calls together should take 2 * (1/2) 3 = 1/4 of the time of the direct approach, giving an upper bound of a 4x speedup. As the performance table at the top of this post shows, we can quickly approach this in practice for large RSA sizes where the exponentiations mod p and q dominate the runtime.

That’s all for this installment, but stay tuned for part 2 to hear how these mathematical changes transform the code itself!

If you’re interested in learning more about our approach to maintainable, production-grade cryptography, or hearing about ZeroRISC in general, sign up for our early-access program or reach out at info@zerorisc.com.