Accelerating Post-Quantum Cryptography on OpenTitan-based Designs: Flexible Hardware for a Secure Future

This cross-posting is courtesy of our collaborators at the Max Planck Institute for Security and Privacy (MPI‑SP). Authored by Amin Abdulrahman and Hoang Nguyen Hien Pham, we are sharing it because it informs our high‑performance embedded post‑quantum solution. It clearly lays out some of the design considerations for the transition to post-quantum safety and high quality set of solutions. We’re grateful for the collaboration and look forward to sharing more PQC results in forthcoming posts.

TL;DR: We describe extensions based on the OpenTitan Big Number (OTBN) coprocessor to enable very efficient support for recently standardized lattice-based post-quantum crypto systems, achieving speed-ups of a factor of 6--9x compared to the baseline. The resulting extended design for an Asymmetric Cryptography Coprocessor (ACC) and software implementations targeting the same are open-sourced and slated for adoption by GlobalPlatform's Trusted Open Source Silicon Task Force. Follow-up work has improved ACC performance further and has been integrated within zeroRISC's research fork on PQC for open-source silicon. The implementation of side-channel countermeasures is forthcoming.

The world of security has been and still is observing two paradigm shifts:

- The transition to post-quantum cryptography

- The realization that open source leads to more secure products

The Imminent Need for Practical Post-Quantum Cryptography

Today's widely deployed asymmetric cryptography is at risk: Schemes such as RSA and elliptic-curve cryptography (ECC) are susceptible to attacks using powerful quantum computers, once those become available. Although this threat might be years---or even decades---away, it was essential that the cryptography community, companies, and standardization bodies started acting as early as possible. The reason for this are so-called "Harvest Now, Decrypt Later" attacks in which a (large-scale) adversary may intercept today's communication that is believed to be secure with the intent to decrypt it once a sufficiently powerful quantum computer becomes available.

As a consequence, in 2016, NIST launched a new standardization effort---modeled after its earlier AES and SHA-3 competitions---to identify cryptographic algorithms that run efficiently on today's hardware while remaining secure against future quantum adversaries. This field is known as post-quantum cryptography (PQC).

The release of the final NIST standards for three PQC schemes in 2024 marks a pivotal moment in IT security. The two primarily recommended schemes, ML-KEM (a key encapsulation mechanism) and ML-DSA (a digital signature scheme), are being swiftly picked up by the industry and can already be found in various software, some of which you may even be using! Prominent examples are Google's Chrome browser, Mozilla Firefox, Cloudflare, Signal, and Apple's iMessage.

This growing adoption also signals the importance of efficient and secure implementations of said primitives, including efficient software for devices like smartphones, efficient hardware circuits for items like credit cards, and efficient hardware/software co-designs living in a space in between. However, many PQC schemes like ML-KEM and ML-DSA present significant implementation challenges compared to their relatively simple classical counterparts. Their mathematical structures and operational patterns vastly differ from the classical RSA and ECC algorithms that today's cryptographic hardware accelerators were designed to support. We consider bridging this gap as critical: our work shows that implementations of post-quantum algorithms on "classical" secure hardware/software co-designs are prohibitively slow for production applications.

Therefore, our research addresses a central question for the hardware security community: How can we enable high-performance post-quantum cryptography on existing, general-purpose secure hardware platforms with modest modifications? This question is not only academically relevant but also of increasing practical importance as migration plans for PQC in industry and governments accelerate.

In the remainder of this blog post, you will find out how we solved this question from a technical perspective, explaining our approach and presenting parts of our results.

Open-Source Silicon

Secure hardware is ubiquitous in our everyday lives. It's part of our smartphones and laptops, and some of you might even own dedicated security tokens like a Yubikey or SoloKey. In contrast to cryptographic software implementations, open and publicly auditable hardware is a rarity. The OpenTitan project was the first coordinated effort that aimed to change this by "building a transparent, high-quality reference design [...] for silicon root of trust (RoT) chips" [2], to facilitate trust and security by providing public design access. Open-source silicon projects enable the research we are doing at MPI-SP: We can try, evaluate, and even extend open designs as part of our research and make the implementation and results of our research freely available to generate a real-world impact. We see this shift to openness as a major step in the domain of hardware security, and with chips based on open-source silicon soon becoming commercially available, it has been proven that building a business and open-sourcing your designs are not in contradiction.

Open-Source Silicon as a Platform for PQC Innovation

OpenTitan is a monolithic, RISC-V-based open-source hardware root-of-trust with contributions from many parties [2] and is on track to enter mass deployment in devices such as future Chromebooks [3].

The source codebase has multiple useful, standard cryptographic accelerators. Among these, there is an AES core, a KMAC accelerator that can be used for computing SHA3 and its XOF-mode SHAKE, and most importantly to our work, the big number coprocessor OTBN, specialized for accelerating asymmetric cryptography such as ECC and RSA. Various layered countermeasures against side-channel and fault injection attacks, useful for secure embedded systems, were implemented for this. These include data-path blanking, data integrity protection, and secure wiping [4].

As we transition from classical to PQC, many real-world systems are expected to require hybrid operation---simultaneous use of both classical and PQC---for the foreseeable future, further emphasizing the need for a flexible and extensible hardware approach. Legacy systems will also benefit from this flexibility as an immediate transition to PQC for all applications is not expected.

We took the existing coprocessor, which we refer to as the baseline coprocessor (BC), as a starting point for a more flexible coprocessor. We call our augmented design the asymmetric cryptography coprocessor (ACC), as it adds acceleration for post-quantum cryptography in addition to accelerating traditional asymmetric cryptography. ACC's targeted modifications address specific performance bottlenecks of lattice-based PQC, while preserving the flexibility and extending the security properties of the original design.

Designing the ACC

The BC offers a RV32I-inspired RISC-V instruction set alongside custom big-number instructions operating on 32 registers of 256 bits each. Since it is programmable, extending the instruction set architecture (ISA) is a natural approach to enabling PQC support. We begin by analyzing the performance bottlenecks in PQC software running on BC, then propose a set of ISA extensions for the ACC that mitigate these bottlenecks. Throughout our work, we adhere to the original design philosophy of generality and flexibility rather than overly specialized solutions.

We approach this task in two steps:

1. Profiling Software-Only PQC Implementations on BC

We first developed assembly-level software implementations of ML-KEM and ML-DSA, including most state-of-the-art optimization techniques introduced in previous work. The profiling of this baseline allowed us to identify the two main bottlenecks:

- Hashing (SHA3/SHAKE): The cryptographic hash functions required in both ML-KEM and ML-DSA consumed the majority of execution cycles, often over 50%.

- Polynomial Arithmetic: (modular) multiplications, additions, and subtractions on small, typically 16 or 32-bit, integers, for example, in the Number Theoretic Transform (NTT), were also significant contributors to runtime.

These findings, although consistent with previous research on PQC on other platforms (e.g., Cortex-M4), are particularly pronounced on BC coprocessor, which is optimized specifically for operations on large integers in contrast to high-throughput parallelism over small integers.

2. KMAC Interface & SIMD ISA Extensions for Polynomial Arithmetic

The ACC addresses both bottlenecks through two complementary extensions:

KMAC Interface. We designed and implemented a direct interface between BC and the high-performance KMAC core, allowing cryptographic operations to offload hash calculations securely and efficiently, without exposing the secret state to less protected parts of the system. This change alone enables speedups of more than 5x for ML-KEM key generation.

SIMD Instructions. To address the polynomial-arithmetic bottleneck, we introduced carefully chosen single-instruction-multiple-data (SIMD) instructions into the instruction set architecture. These enable parallel modular addition, subtraction, and multiplication of 16- or 32-bit elements packed within the 256-bit wide registers.

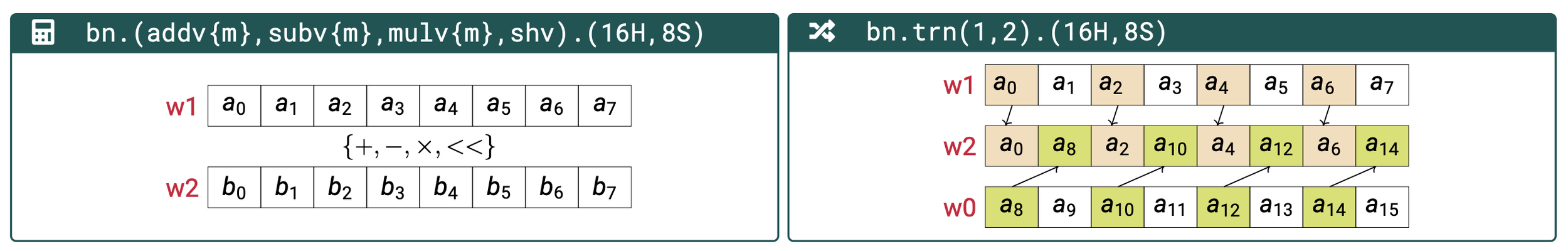

In the following, the .16H option means a 256-bit wide register is viewed as a

vector of 16 16-bit elements, while .8S means 8 32-bit vector elements. m

stands for modular reduction, and l stands for lane mode (explained below).

Our proposed instructions are:

bn.addv{m}{.16H,.8S}: Vectorized addition. Modular reduction is conditional subtraction of the modulusq.bn.subv{m}{.16H,.8S}: Vectorized subtraction. Modular reduction is conditional addition ofq.bn.shv{.16H,.8S}: Vectorized shift.bn.mulv{m}{.l}{.16H,.8S}: Vectorized multiplication. Withm, the Montgomery multiplication is performed. Withl, all the elements of the first source vector are multiplied by one element of the second source vector of a given index.bn.trn{1,2}{.16H,.8S}: Vector transpose. With1, even-position elements of the first and second source vectors are interleaved in the destination vector. With2, it is the same operation, but for odd-position elements instead.

The proposed instructions can be visualized as below:

Proposed Vectorized Instructions

These instructions are well-suited to optimize core routines such as the NTT and base multiplication, which are the most performance-critical routines to ML-KEM and ML-DSA, next to the hashing.

Importantly, unlike prior work that focused on tightly coupled accelerators for specific algorithms resulting in scheme-tailored instructions, the ACC's ISA extensions are generic. They enhance not only ML-KEM and ML-DSA, but are also broadly applicable to a large class of lattice-based and symmetric cryptographic algorithms as long as modular operations are a significant bottleneck. This maximizes the return on hardware investment and supports future cryptographic agility.

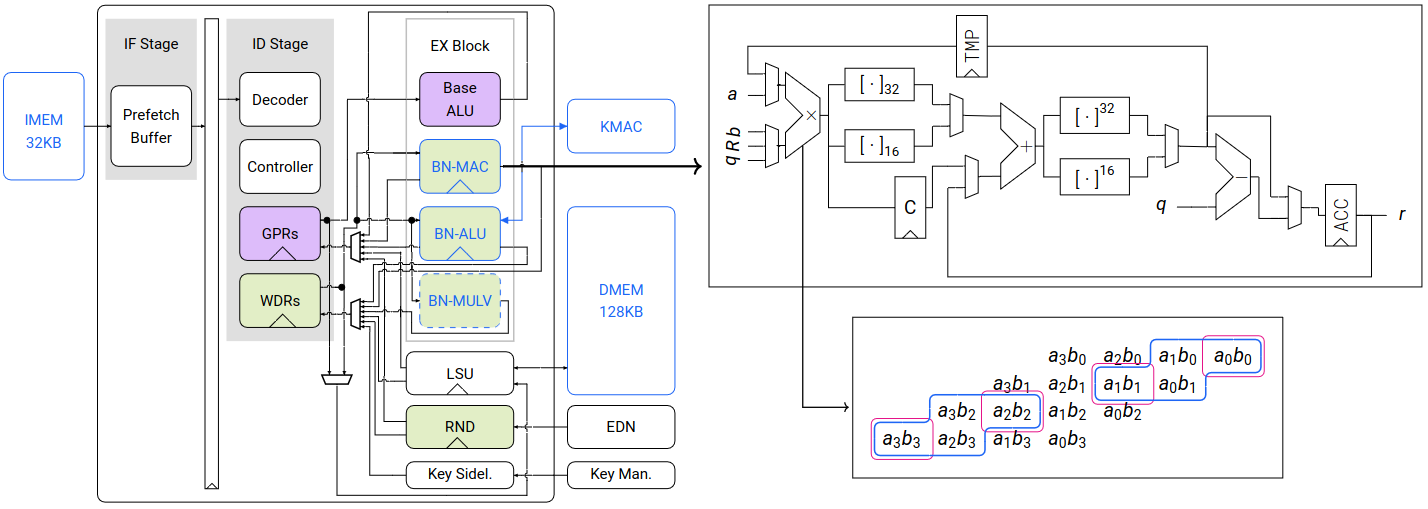

Modifying the Hardware for the New Instructions

Now, let us get to the main question: how can hardware costs be kept low for such powerful instructions? The answer is: by intelligently reusing existing resources!

Below is the graph showing the BC pipeline. The purple blocks relate to the RV32I portion of the ISA, while the green ones are related to the big-number ISA, operating on the 256-bit registers. The blue border indicates which block is modified, while the dashed one shows which block is optional.

Visualized BC’s Pipeline

For vectorized addition and subtraction, we split the existing 256x256-bit

adder in the BN-ALU unit to 16 16x16-bit adders. From these small adders, 8

32x32-bit, 16 16x16-bit or 256x256-bit sums can be computed depending on their

input carries. For vectorized shift and vector transpose, we reuse the

BN-ALU's functional unit for shifting.

For vectorized multiplication, our main approach was to extend the existing

64x64-bit multiplier in the BN-MAC unit to compute either one 64x64-bit, two

32x32-bit, or four 16x16-bit multiplications by splitting the 64x64-bit product

and combining appropriate partial products. For modular multiplication, the results

are further reduced using Montgomery multiplication, which takes 3 cycles.

Overall, one bn.mulvm instruction takes 12 cycles for computing 16 16x16-bit

(.16H variant) or 8 32x32-bit (.8S variant) modular multiplications.

Similarly, one bn.mulv takes 4 cycles for both variants.

As a design-space exploration, the blue-dashed BN-MULV block in the graph

above represents an alternative for vectorized modular multiplication. While

this significantly accelerates software performance by reducing bn.mulv{m} to

a single cycle, it incurs a substantial increase in hardware cost.

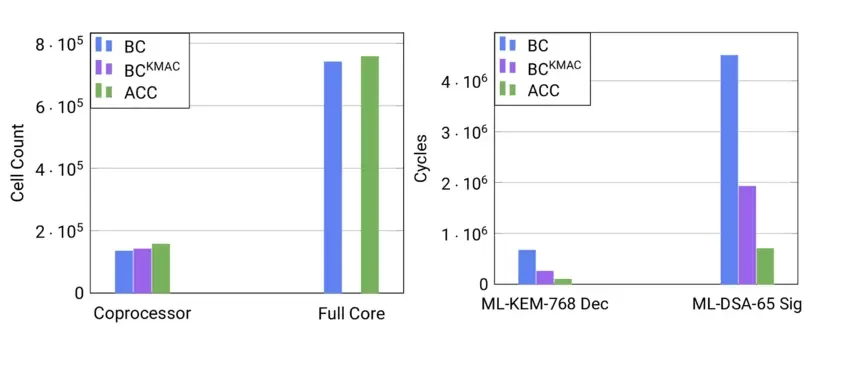

Key Results: ACC's Software Speedup and Hardware Cost

We compared the ACC against our own software implementations on the BC coprocessor and against other PQC projects leveraging OpenTitan IP. We also compared against hardware/software co-designs on different platforms, most of which are less versatile or use scheme-specific accelerators.

The combined effect of the ACC's extensions is substantial:

- Software Performance: With the KMAC interface and our SIMD extensions, ML-KEM and ML-DSA achieve a speedup by a factor between 6x and 9x for different operations and parameter sets compared to the implementation on BC. For example, verifying an ML-DSA signature is not only feasible on the ACC but also faster than verifying an ECC signature at an equivalent "classical" security level (e.g., ML-DSA-44 verification is 41% faster than ECDSA-P256).

- Hardware Overhead: The above speedup in software is achieved with only an increase in cell count of less than 17% for the ACC compared to BC, amounting to less than 3% increase in the area of the full core.

- Side-channel Resistance: The ACC's extensions were implemented with the side-channel countermeasures also present in BC. Along with our collaborators, we will release additional masking or blinding countermeasure implementations in the future.

- Generality and Flexibility: The ACC's SIMD instructions accelerate a wide range of cryptographic primitives. Future schemes (and potential revisions of existing ones) can be supported by software updates, not costly hardware redesigns.

BCKMAC: BC with our KMAC interface. ACC: BCKMAC with our ISA extensions.

In summary, our work on the ACC demonstrates that enabling embedded PQC is not only possible, but also can be achieved efficiently at reasonable hardware cost while retaining flexibility.

Follow-up Work

Since the publication of the paper, several pieces of follow-up work have been carried out, including:

- Stack optimization for ML-DSA aimed at reducing memory consumption, which is critical for lowering hardware cost and for enabling first-order masked ML-DSA on ACC, since masking incurs significant memory overhead. This optimization has been implemented by zeroRISC and is available here.

- "Improving ML-KEM and ML-DSA on OpenTitan - Efficient Multiplication Vector Instructions for OTBN" further improves the current 64x64-bit multiplier to compute all sixteen 16x16-bit multiplications instead of only four. Together with shifting the modular multiplication from hardware back to software through new vector multiplication instructions and better vector adder designs, the authors achieve speedups of up to 17% for both ML-KEM and ML-DSA, while preserving the same area and improving the frequency of the whole design.

- Our work has served as a partial foundation for the approaches and implementations presented in [7,8]. Building on our code base, [7] implements some masking gadgets on BC.

On-going and Future Work

There are still many opportunities for improvements regarding our current design and its interplay with PQC. We are looking forward to continuing this line of work for the following ideas:

- Extending support to other post-quantum schemes (e.g., UOV, MAYO, HQC, Classic McEliece) and hybrid-, and homomorphic cryptography. As long as other PQC schemes heavily rely on modular operations on small integers or on hashing, it is worth exploring the performance improvements by using our ISA extension and the KMAC interface.

- Leveraging new vector instructions for efficient symmetric cryptography, such as SHA-2/SHA-3 variants and stream ciphers.

- Since side-channel attacks are being researched thoroughly nowadays [9,10], a masked implementation of ML-KEM and ML-DSA is of high importance.

- Enabling formal verification for crypto code running on the ACC is also an important next step. For example, re-implementing ML-KEM and ML-DSA in the Jasmin language. Ongoing work by Arranz-Olmos is aimed at enabling this.

Conclusion

The cryptographic landscape is undergoing a rapid transformation with research accelerating for two critical and interconnected areas: post-quantum cryptography and the resilience of its implementations.

The demand for secure hardware PQC solutions highlights the crucial role of open-source silicon initiatives, whose transparency allows us researchers to push innovation and adapt to the evolving challenges.

Our work, while one of many contributions within this larger research effort, directly addresses the potential of open-source silicon. With the ACC, we demonstrate that by strategically equipping open-source silicon designs with versatile and efficient hardware features, it is possible to achieve high-performance post-quantum cryptography. Crucially, we show that these enhancements can be integrated at a reasonable hardware cost.

Finally, we would like to thank all the open silicon contributors out there for pursuing such an amazing idea and shout out to other co-authors and many people involved in this project for their help and feedback.

Craving for more?

If you are interested in this work and want to explore the juicy details, our paper "Towards ML-KEM and ML-DSA on OpenTitan" is published at IEEE S&P 2025. We also uploaded a more detailed version of the paper to the IACR eprint archive. All software and hardware used in this research are made publicly available in our GitHub repository.

For readers who are curious about other approaches trying to bring PQC to open-source silicon, you can check out [5,6]. We also highly encourage you to check out the fantastic blog posts by zeroRISC, major contributors to OpenTitan's original cryptography implementations, on the practical deployment of embedded post-quantum and classical cryptography.

Thank you for reading this very first blog post of MPI-SP!

Please get in touch with us, if you ...

- ... are looking for collaborations on open-source secure silicon.

- ... can imagine writing a Bachelor's or Master's thesis with us on open-source silicon.

- ... would like to work as a student assistant on topics around PQC on open-source silicon, high-performance software implementations, or hardware design.

- ... have any feedback on this blog post and on how we can make our research more accessible to you.

Email:

- Amin Abdulrahman (amin@abdulrahman.de)

- Hoang Nguyen Hien Pham (hoang-nguyen-hien.pham@mpi-sp.org)

References

[1] Amin Abdulrahman, Felix Oberhansl, Hoang Nguyen Hien Pham, Jade Philipoom, Peter Schwabe, Tobias Stelzer, and Andreas Zankl. "Towards ML-KEM & ML-DSA on OpenTitan." In 2025 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), pp. 1-19. IEEE, 2025. https://eprint.iacr.org/2024/1192

[2] OpenTitan. "OpenTitan". https://opentitan.org/

[3] Nuvoton. "Nuvoton Develops OpenTitan® based Security Chip as Next Gen Security Solution for Chromebooks". https://www.nuvoton.com/news/news/all/TSNuvotonNews-000514/

[4] OpenTitan. "Introduction to OTBN". https://opentitan.org/book/hw/ip/otbn/doc/otbn_intro.html

[5] Emma Urquhart and Frank Stajano. "Acceleration of Core Post-quantum Cryptography Primitive on Open-Source Silicon Platform Through Hardware/Software Co-design." In: Cryptology and Network Security. CANS 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 14905. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-8013-6_7

[6] Tobias Stelzer, Felix Oberhansl, Jonas Schupp, and Patrick Karl. "Enabling Lattice-Based Post-Quantum Cryptography on the OpenTitan Platform." In Proceedings of the 2023 Workshop on Attacks and Solutions in Hardware Security (ASHES '23). Association for Computing Machinery, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1145/3605769.3623993

[7] Filali Hakim. "Power Side-Channel Evaluation and Hardening of PQC Algorithms on OpenTitan." Master Thesis. 2025. https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/entities/publication/efd66d6b-69ce-4067-b516-fe6d0d5a934a

[8] Pascal Etterli. "Design and Optimization of a PQC ISA Extension for OTBN". Semester Project. 2024. https://lowrisc.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/etterli_design_2024_report.pdf

[9] Olivier Bronchain and Gaëtan Cassiers. "Bitslicing Arithmetic/Boolean Masking Conversions for Fun and Profit with Application to Lattice-Based KEMs." IACR Transactions on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems. 2022, 4 (Aug. 2022), 553-588. https://eprint.iacr.org/2022/158.pdf

[10] Jean-Sébastien Coron, François Gérard, Tancrède Lepoint, Matthias Trannoy, and Rina Zeitoun. "Improved High-Order Masked Generation of Masking Vector and Rejection Sampling in Dilithium." IACR Transactions on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems. 2024, 4 (Sep. 2024), 335-354. https://eprint.iacr.org/2024/1149.pdf